I want to ride to the ridge where the West commences

I can’t look at hobbles and I can’t stand fences

Don’t fence me in.

-Cole Porter

The places we love call to us because they are, in fact, “the landscape of our soul.”

I don’t mean the landscape of our childhood or of some special memory. The landscapes we love speak powerfully to us, they call to us, because the country corresponds to the actual terrain of our interior world, the landscape of our soul. That is why one man feels such a deep connection to the deserts of the Southwest, while another feels it with the ocean, or hardwood forests, or the high country above timberline. When we go there, we feel as if we have come home.

I find the same thing to be true of art—when you find a painter or a style that you really love, you’re also encountering something that speaks to the geography of your own soul.

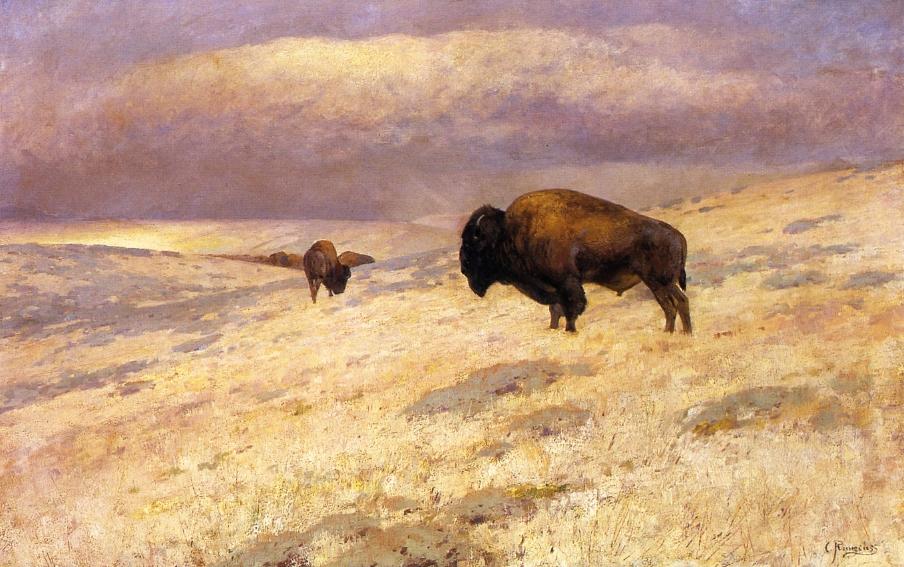

For me, it has always been Western art. Not the cheesy John Wayne-on-black-velvet stuff you see at swap meets. I’m talking especially about the early classics—Remington, Russell, Moran, Runguis—painters who captured the heart of the West in the late 1800s. Their work expresses the ethos of the landscape and lifestyle that have a mythic place in my heart.

The more I looked into their lives, the more I loved the story they lived.

Runguis’s biography is entitled Fifty Years with Brush and Rifle. I bought it for the title alone, partly because I thought, That is a fabulous life, and partly because of a conversation I had recently had. “You’re the first thoughtful, artistic person I’ve ever met who also hunts.”

The comment was made with wonder and confusion by a very reflective man, a student of human nature. The surprise he felt in the apparent “obvious” contradiction of “artistic” and “hunter” is a reflection of assumptions held by many thoughtful people in the 21st Century, whose lives have become almost completely separated from wild places and from the sources of their food. But it would have been foreign to the people who lived before the age of TV dinners and frozen burritos.

Runguis was a hunter and painter; he lived out in the woods for months at a time, in the Wind River Range in Wyoming, pursuing big game, drawing sketches, and studying the wildlife that he would become so famous for.

Whereas many so-called “western artists” stayed in the East and painted their horses using as models the ones you see on children’s carousels. Born and trained in Germany, Runguis cut all ties with the Old World after his first hunting trip to the Rocky Mountain west.

“My heart is in the West,” he explained. I know exactly what he meant—he found the landscape of his soul.

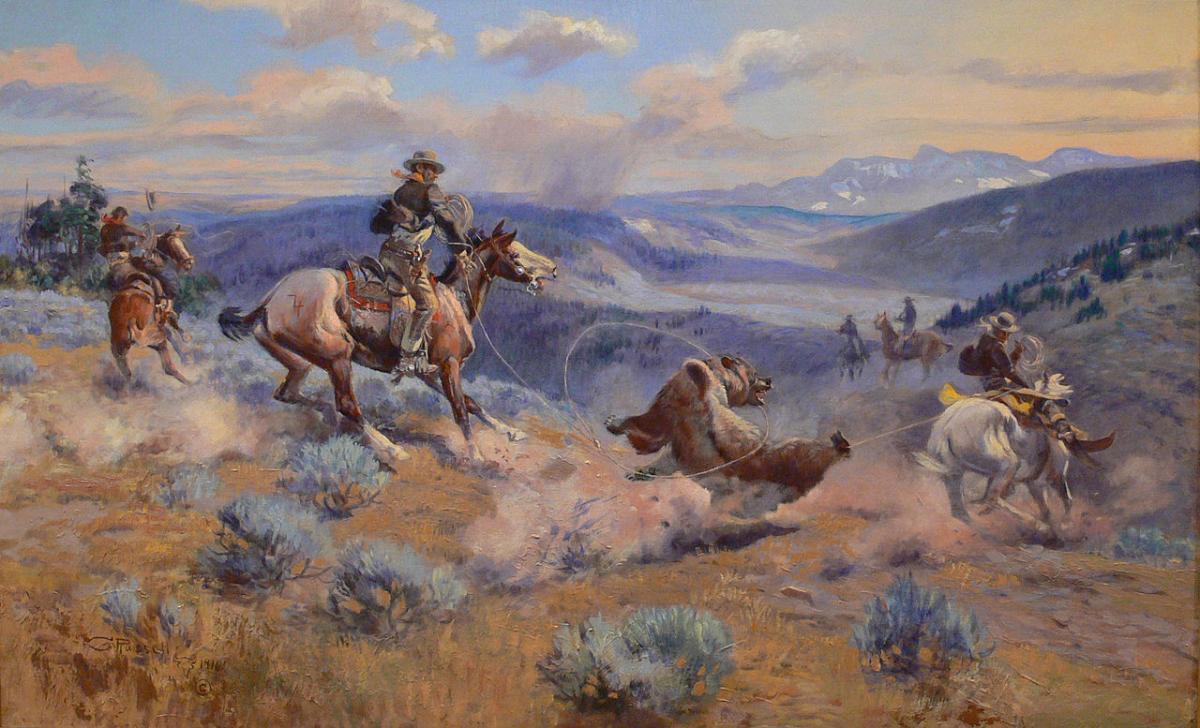

Charlie Russell is another fascinating story—he came out West to work as a cowboy and live among the hard characters he would so powerfully portray. Born in then a rather tame Missouri, he dreamed about the Wild West and like many boys after him read every story about it he could lay his hands on.

The call of the West seized him at sixteen, so he dropped out of school and went to work on a ranch in Montana. Like Runguis, he never looked back, moving from ranch to ranch as a hired hand. In 1888 he lived with the Blackfeet Indians, and much of his work portrays an intimate knowledge of the Native American way of life.

What I love about these guys is that they plunged into the world they would eventually paint. Their knowledge was firsthand; it was hard-earned, and it gives me a respect for their work. Russell’s painting “Loops and Swift Horses” seems incredible—except to the men who lived in the saddle, and yes, did this very thing. (I know some old cowboys who would chase down bull elk and lasso them.)

Remington spent a lot of time living and painting among the U.S. Cavalry, and many of his works are based on true stories he heard from officers. Unlike Russell, who lived among the Indians and was welcomed as one of their own, Remington was influenced with an “anti-red man” bias from the soldiers he hung out with, and some of his work romanticizes the accounts from a Cavalry point of view. But overall, his paintings and sculptures are worthy to have become iconic, mythic, nearly synonymous with the Old West.

Thomas Moran paints in the style of the “Hudson River School” he was a part of, but his work out West is what earned him a national reputation. I love his “Cliffs of the Green River” (above). What’s really cool about Moran’s story is that his work helped establish Yellowstone as a National Park. He came west with the Hayden expedition in 1871, and painted both the Yellowstone and Teton regions. It was those images that helped win national support for the protection of Yellowstone. (Mt Moran, named after him, is our favorite peak in the Tetons).

But I’ve been writing on the landscape of my heart. The real question is, what is yours? Has it occurred to you that the geography you love is a mirror image of the landscape of your soul?

It might be good to go back and look at photographs, or visit the place again, and let that thought take you deeper. I would do the same with art—don’t just put up any old image in your home or office. Find those works that call to and feed your soul. There is a terrain in you that needs to find its counterpart in the world.

Share